#6: The Language of AI: How ChatGPT Actually Reads Your Words

Why your AI bill depends on invisible text fragments you never knew existed?

Hi, it’s Sangam!

It has been a few weeks. I was using Google AI Studio and Bolt, and was wondering how exactly these tokens are being deducted. And, the whole math is very interesting. Let’s go through the fundamentals here.

When you type "Hello world!" into ChatGPT, something fascinating happens before the AI even begins to "think." Your simple greeting doesn't reach the model as two words and punctuation. Instead, it arrives as a sequence of mysterious fragments: ['Hello', ' world', '!']—three distinct pieces called tokens.

This invisible transformation is tokenisation, the most crucial yet least understood process powering every AI conversation. It's the difference between paying $10 or $100 for the same API call.

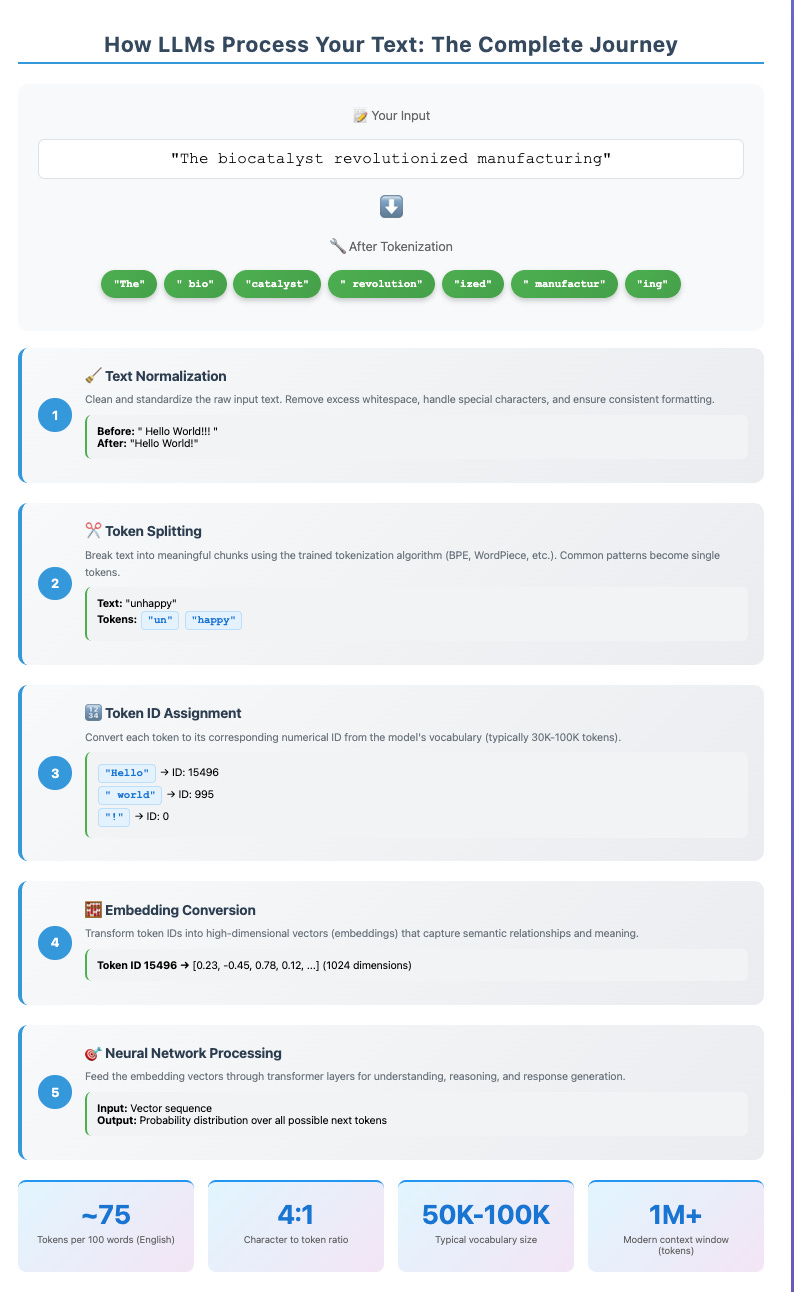

LLM Tokenization

Tokenisation is the process of breaking raw text into smaller units called tokens, which LLMs use to understand and generate language. These tokens can be words, subwords, characters, punctuation, or whitespace.

It's why ChatGPT stumbles over "3.11 vs 3.9" comparisons. And it's the lens through which all AI systems see our world.

Language Understanding: LLMs can’t process raw text. Tokenization converts text into numerical IDs for the model to interpret.

Vocabulary Management: Helps models handle rare or unseen words by breaking them into subwords (e.g., “biocatalyst” → “bio” + “catalyst”).

Efficiency: Fewer tokens = faster, cheaper processing.

Performance: Good tokenization = better comprehension, especially for code, typos, non-English text.

The Misunderstanding

Here's a story that illustrates why tokens matter: Last year, a startup building a multilingual customer service bot discovered their API costs were hemorrhaging cash. Their English conversations cost roughly $2 per 1,000 customer interactions. But Japanese conversations? Nearly $12 for the same service.

The culprit wasn't more complex queries or longer responses. It was tokenization. While English words typically convert to 1-2 tokens each, Japanese text often requires 3-4 tokens per word. The AI was essentially charging them 300% more to process the same semantic content—all because of how the underlying technology chops up different languages.

This isn't an edge case. With AI companies collectively processing trillions of tokens monthly, tokenization inefficiencies represent billions in hidden costs across the industry.

How AI Actually Sees Language

To understand tokens, imagine you're an alien who has never seen human writing. Someone hands you the sentence "The biocatalyst revolutionised manufacturing." Your job: break this into the smallest meaningful pieces possible.

You might intuitively separate it like this:

"The" (common word, keep whole)

"bio" + "catalyst" (complex word, split into recognisable parts)

"revolution" + "ized" (root word plus suffix)

"manufact" + "uring" (another root-suffix split)

Congratulations—you've just performed tokenisation. This is exactly how AI models like GPT-4 process text, except they do it for vocabularies containing 50,000-100,000 possible token pieces.

The brilliance lies in the efficiency. Instead of needing a separate entry for every possible word in every language (impossible), AI models learn a finite set of reusable building blocks. When they encounter "extraordinary," they can understand it as "extra" + "ordinary"—two familiar pieces rather than one unknown word.

The Token Economy

Tokens are the currency of AI. You don't pay for words, characters, or thoughts—you pay for tokens. And the exchange rate varies wildly:

English text: ~1 token per 0.75 words

Python code: ~1 token per 0.5 words

Japanese text: ~1 token per 0.25 words

Complex math expressions: Unpredictable fragmentation

Consider this real example:

"Calculate 3.14159" = 4 tokens:

["Calculate", " 3", ".", "14159"]"Calculate π" = 3 tokens:

["Calculate", " π"]

The number π, despite representing the same mathematical concept, gets shredded into fragments while the symbol stays whole. This is why AI models often struggle with numerical reasoning—they're not seeing "3.14159" as a single number, but as four disconnected pieces.

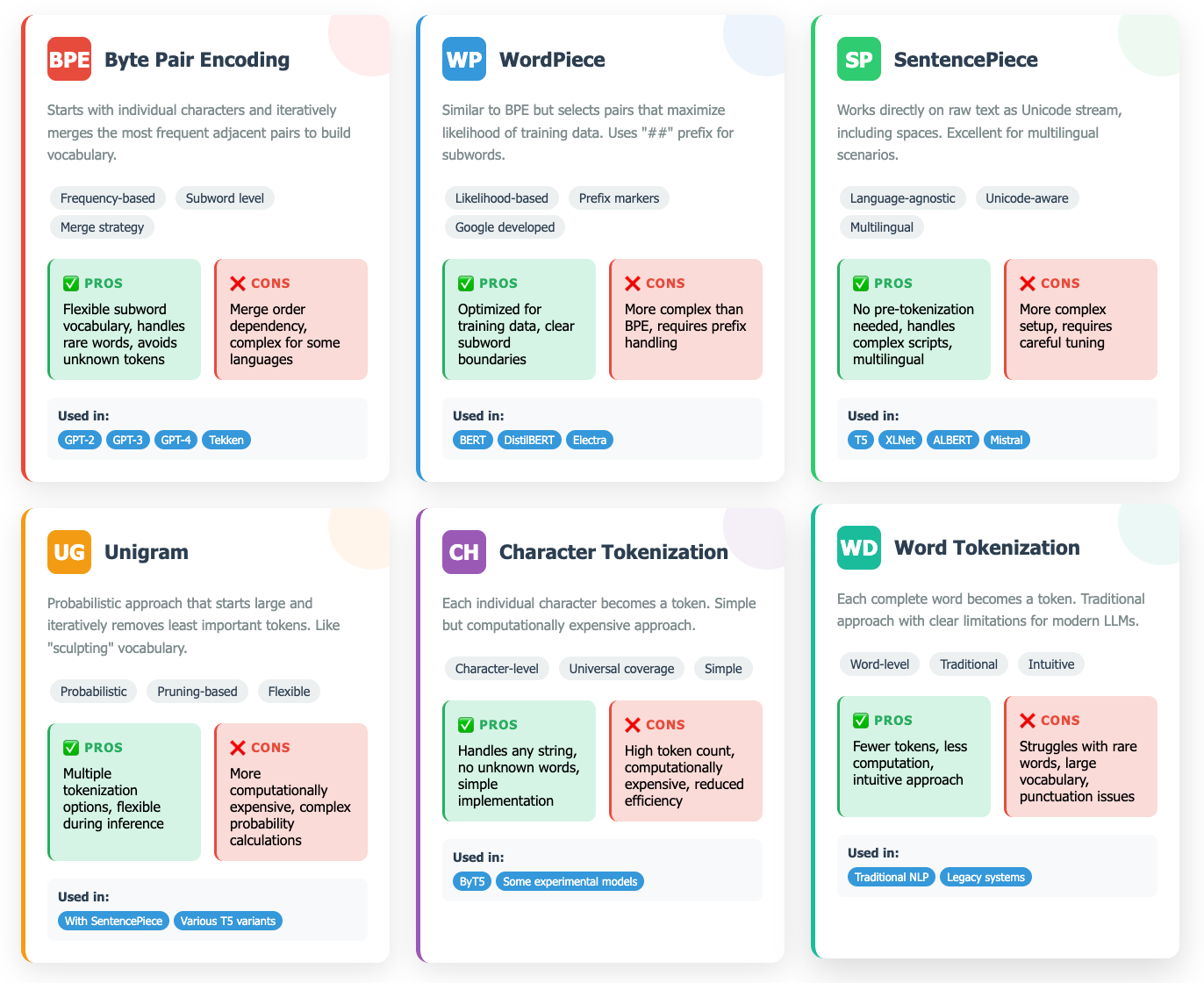

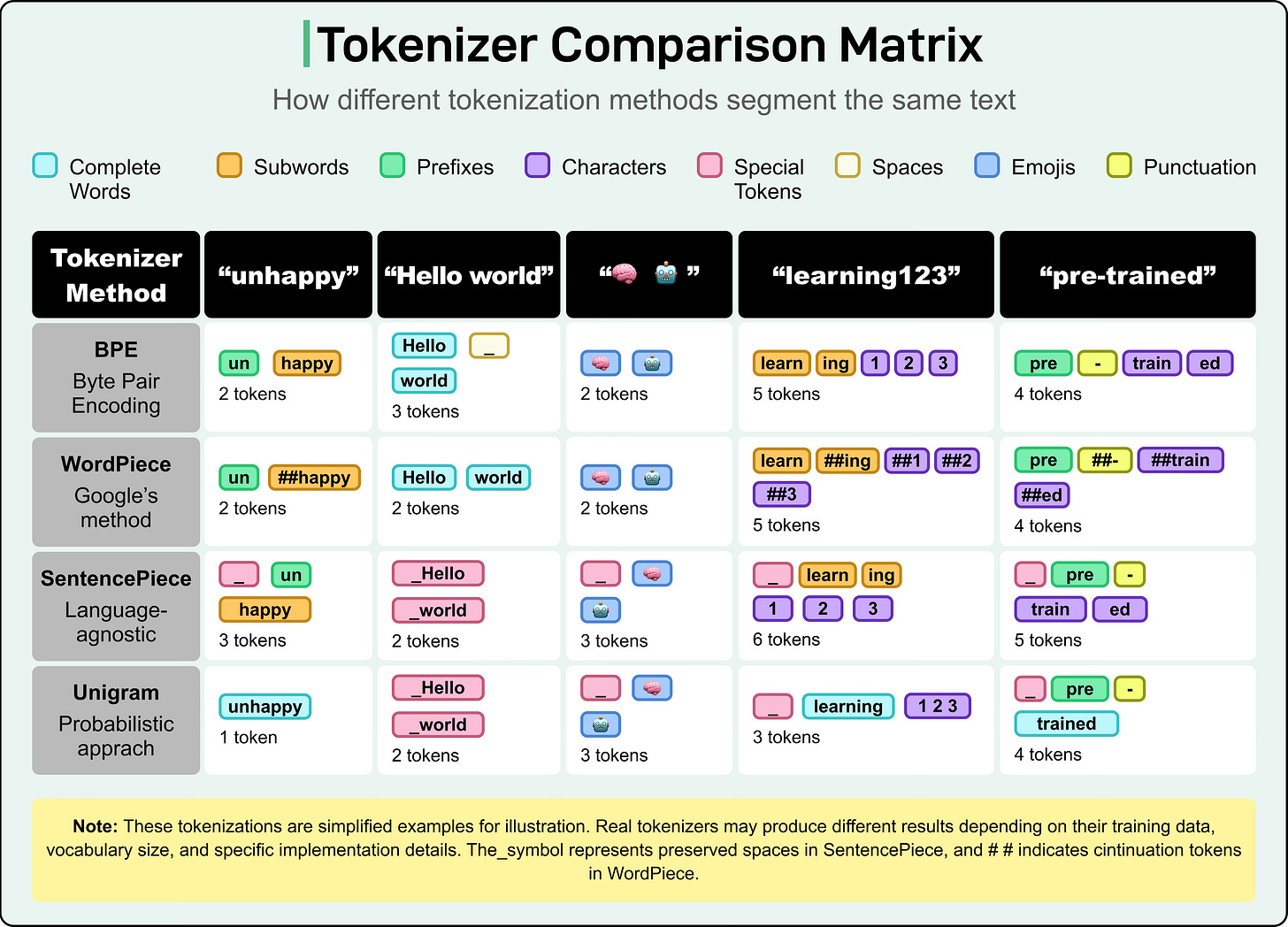

Tokenization Methods

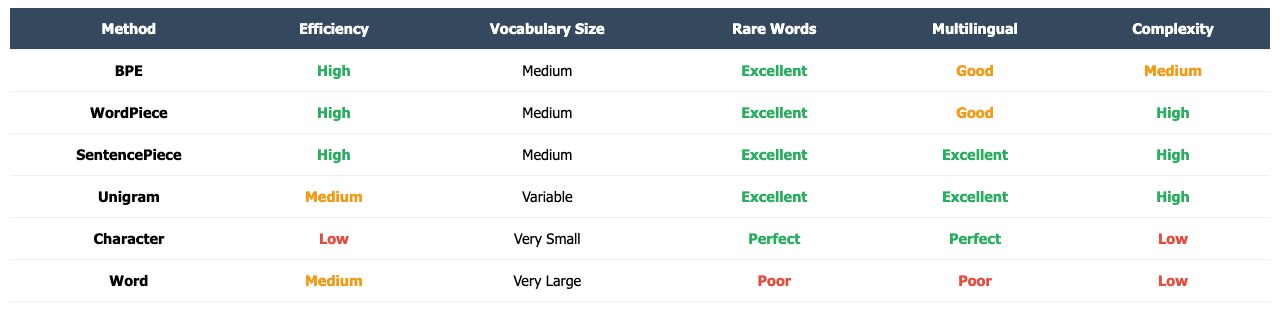

The specific method used varies by Large Language Model (LLM). There are numerous tokenization methods, and they are crucial because they determine the model's vocabulary, processing efficiency, and performance.

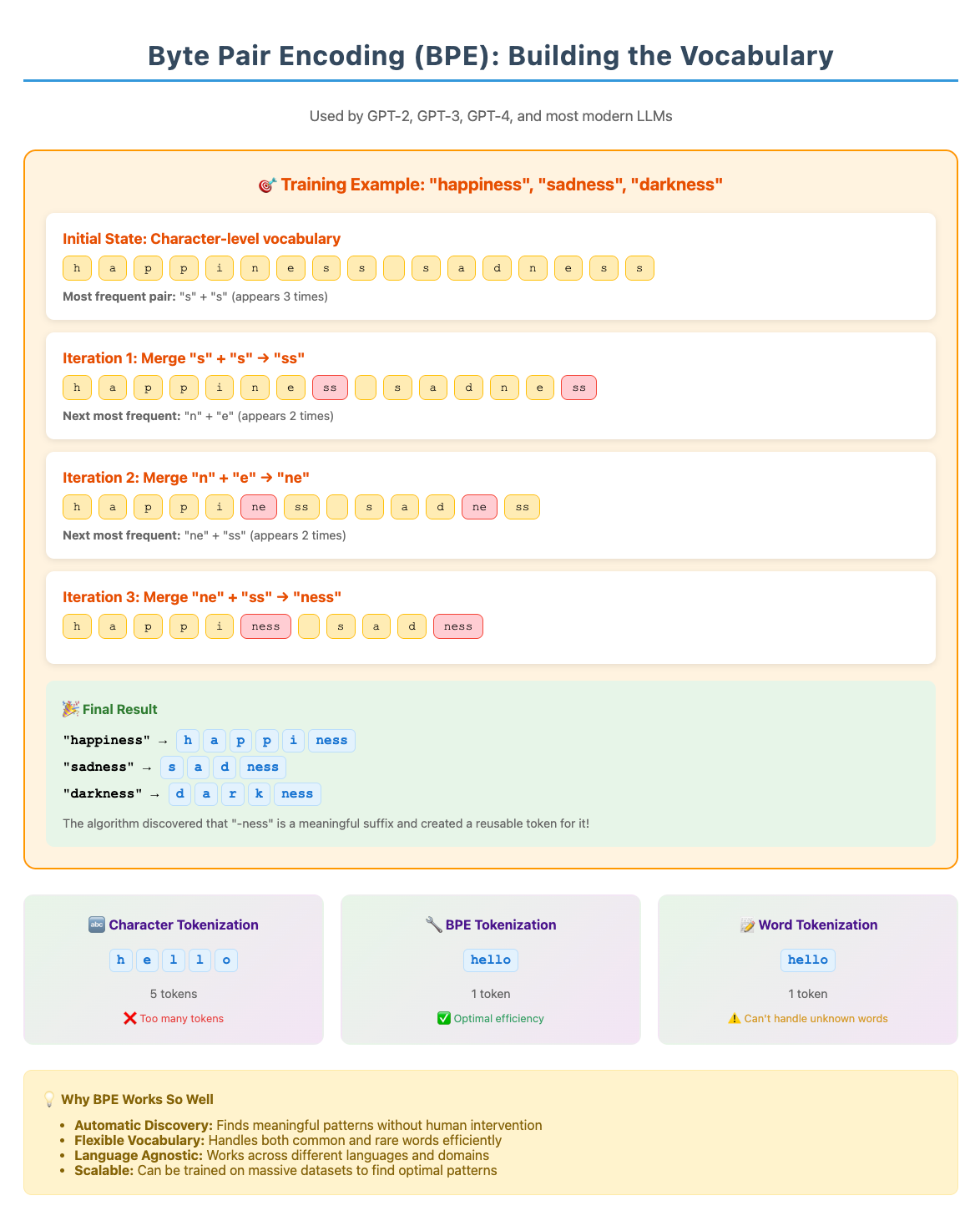

Byte Pair Encoding (BPE)

The dominant tokenization method today, Byte Pair Encoding (BPE), emerged from data compression research. It works like finding the most popular letter combinations in a massive library, then creating shortcuts for them.

Start with individual characters:

a,b,c,d...Find the most common pairs: maybe

"th"appears millions of timesCreate a new token:

"th"becomes token #50,001Repeat until you have your desired vocabulary size

The result? A vocabulary that naturally captures the statistical patterns of language. Common combinations like "ing," "the," and "tion" become single tokens, while rare words get broken into recognizable parts.

Google's competing approach, WordPiece, powers models like BERT. Instead of just counting frequency, it optimizes for maximum likelihood—choosing merges that make the training data most probable. It's like BPE with a statistics PhD.

The Context Window: AI's Photographic Memory Limit

Every AI model has a "context window"—the maximum number of tokens it can consider at once. Think of it as the model's working memory.

GPT-2 (2019): 1,024 tokens (~750 words)

GPT-3 (2020): 4,096 tokens (~3,000 words)

GPT-4 (2023): 128,000 tokens (~96,000 words)

Claude 3 (2024): 1,000,000 tokens (~750,000 words)

This limit affects everything. It determines whether an AI can read your entire document, how much conversation history it remembers, and whether it can maintain coherence across long responses.

But here's the twist: efficient tokenization means more content fits in the same window. If your tokenizer represents text with fewer tokens, you can feed the AI longer documents or maintain longer conversations within the same computational budget.

When Tokenization Breaks Down

The token system creates fascinating edge cases that reveal how differently AI sees our world:

The Emoji Explosion: A single 🧠 emoji might consume 3-5 tokens, depending on the model. Your brain emoji costs more to process than the word "brain."

The Math Mystery: Why do AI models struggle with "Which is bigger: 3.11 or 3.9?" Because they see ["3", ".", "11"] vs ["3", ".", "9"]—not decimal numbers, but disconnected symbol fragments.

The Multilingual Tax: English speakers get subsidized AI. A Chinese user pays roughly 2-3x more tokens for the same semantic content because Chinese characters require more tokens per concept.

The Code Catastrophe: Programming languages weren't designed for AI tokenization. A simple Python function might get chopped into dozens of tokens, with operators, indentation, and identifiers fragmented in unexpected ways.

The tokenization revolution is just beginning. Researchers are developing:

Adaptive Tokenization: Systems that adjust their vocabulary in real-time based on the content they're processing. Talking about biology? The tokenizer temporarily optimizes for biological terms.

Tokenizer-Free Models: Experimental approaches like ByT5 process raw bytes directly, eliminating the token layer entirely. Every possible character becomes processable without vocabulary limits.

Multimodal Tokens: Future models will tokenize images, audio, and video into the same token space as text, enabling truly unified AI reasoning across all media types.

Understanding tokenization transforms how you interact with AI:

For Prompt Engineering: Shorter, common words are more "token-efficient" than longer, rare ones. "Use" costs less than "utilize."

For API Budgeting: Count tokens, not words. Use online tokenizers to estimate costs before building applications.

For Debugging AI Behavior: When AI acts strangely with numbers, code, or foreign languages, tokenization is often the culprit.

For Product Strategy: If you're building AI products, tokenization efficiency can be a major competitive advantage—or disadvantage.

Tokens are the invisible infrastructure of the AI economy. They determine the cost of every API call, the length of every conversation, and the accuracy of every AI response. They're why some languages are second-class citizens in AI systems, why mathematical reasoning remains challenging, and why your AI bill might be higher than expected.

As AI becomes increasingly central to how we work and communicate, understanding this hidden layer becomes crucial. The companies that master tokenization efficiency will build faster, cheaper, more capable AI products. Those that ignore it will wonder why their competitors somehow deliver better performance at lower costs.

The next time you chat with an AI, remember: it's not reading your words. It's processing a stream of carefully crafted tokens—and in that difference lies both the magic and the limitations of artificial intelligence.

That is all for today.

See you next week.

I adore you.

— Sangam

Follow me on X, LinkedIn and Medium.

The tokenization algorithms described here process trillions of tokens daily across services like ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini. As AI capabilities expand, these invisible text fragments will increasingly determine which applications are economically viable and which languages and use cases get left behind.

Glossary

Adaptive Tokenization: A modern tokenization method that iteratively refines tokenization strategies based on real-time assessments of model performance during training, dynamically adjusting token boundaries.

API (Application Programming Interface): A set of defined rules that enable different software applications to communicate with each other. In LLMs, APIs allow developers to integrate and use LLM capabilities in their own applications.

Byte Pair Encoding (BPE): A widely used subword tokenization algorithm that builds a vocabulary by iteratively merging the most frequent pairs of characters or subwords in a text corpus.

Byte-Level BPE: A variant of BPE that works directly with UTF-8 bytes rather than Unicode characters, ensuring that any possible character can be represented and avoiding "unknown token" issues.

Byte-Level Processing: A tokenizer-free approach where LLMs process raw UTF-8 bytes directly, using a minimal vocabulary of 256 byte values plus control tokens.

Character Tokenization: A tokenization method where each token consists of a single individual character from the input text.

Context Window: The maximum number of tokens that an LLM can process or consider at once as input and generate as output. This limit affects the model's ability to maintain coherence over longer texts.

Control Tokens: Special tokens used in the encoding process (especially by Mistral AI) to represent specific instructions or indicators, such as message boundaries or tool calls, and are not treated as regular strings.

Decoding: The reverse process of tokenization, where numerical token IDs (output by the LLM) are converted back into human-readable text using the tokenizer's vocabulary.

Deterministic: In the context of tokenization, it means that for a given input text and a specific tokenizer, the output sequence of tokens will always be the same, without randomness.

Dynamic Vocabulary Expansion: Advanced tokenization techniques that allow the vocabulary to adapt at runtime, for example, by creating "hypertokens" for repeated patterns or generating embeddings for novel tokens on the fly.

Embeddings: High-dimensional numerical vectors assigned to each token (or sequence of tokens) that capture their semantic relationships. These vectors allow neural networks to perform mathematical operations and "understand" meaning.

Encode: The process of converting input text into tokens using a tokenizer, and then assigning each token a numerical ID.

Inference: The process where a trained AI model receives new input data (prompt) and generates a response based on its learned patterns. In LLMs, this involves processing input tokens and generating output tokens.

Inter-token Latency (Token-to-token Latency): The rate at which subsequent output tokens are generated by an AI model, influencing the perceived speed and smoothness of the response.

Large Language Model (LLM): An AI model trained on massive amounts of text data to understand, generate, and reason about human language.

Merge Order: The specific sequence in which byte pairs are merged into new tokens during the training of a Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) tokenizer. This order must be followed precisely during inference to ensure correct encoding.

Normalization (Text Normalization): The initial step in tokenization where raw text is standardized by cleaning, lowercasing, and removing inconsistencies to create a uniform base for the tokenizer.

Out-of-Vocabulary (OOV) Tokens: Words or characters that are not present in the tokenizer's predefined vocabulary, which older or simpler tokenizers might struggle to represent.

Probabilistic (LLM inference): Refers to the non-deterministic nature of LLM output generation, where the model predicts the most statistically likely next token, rather than a fixed, predetermined outcome.

Prompt Injection: A security vulnerability where malicious input (e.g., using control token tags as text) can confuse an LLM and cause it to behave in unintended ways.

Regular Expressions (Regex/RegEx): A sequence of characters that define a search pattern, often used in advanced tokenizers to precisely split text based on specific rules (e.g., separating punctuation from words).

Semantic Tokens: In audio applications, a type of tokenizer that captures language or context data instead of simply acoustic information, enabling models to understand the meaning of a sound clip containing speech.

SentencePiece: An unsupervised subword tokenization library developed by Google that works directly on raw text (including spaces) and can implement either BPE or Unigram algorithms, often used for multilingual models.

Subword Tokenization: A tokenization method that divides words into meaningful chunks (subwords) rather than whole words or individual characters, balancing efficiency and vocabulary flexibility.

Tekken (Mistral AI): Mistral AI's newest tokenizer, which uses Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) with Tiktoken, trained on over 100 languages for efficient text and source code compression.

Text Bytes: The numerical representation of text characters in byte form, often using encoding schemes like UTF-8.

Time to First Token: The latency between a user submitting a prompt to an AI model and the model beginning to generate its response, crucial for user experience in interactive applications.

Token: A tiny, discrete unit of data that LLMs process. Tokens can be words, subwords, individual characters, punctuation, or special symbols.

Token ID: A unique numerical integer assigned to each distinct token in an LLM's vocabulary, allowing text to be represented numerically for processing.

Tokenization: The process of breaking down human-readable text into smaller, discrete units called tokens, which LLMs can then process.

Tokenizer-Free Approaches: Novel LLM architectures that eliminate traditional tokenization steps entirely by processing raw text at a byte or character level.

Training (LLM): The process of exposing an LLM to massive amounts of data so it can learn patterns, relationships, and the statistical likelihood of token sequences.

Unigram (Tokenization): A probabilistic subword tokenization method that starts with a large vocabulary of candidates and iteratively removes tokens that least affect the model's ability to represent the training data.

UTF-8 (Unicode Transformation Format - 8-bit): A variable-width character encoding that can represent every character in the Unicode character set, used to consistently transform text into a numerical format (bytes) for computers.

Vocabulary (LLM): The complete set of unique tokens that a Large Language Model has been trained on and can recognize.

Word Tokenization: A tokenization method where the text is split into individual words, typically based on delimiters like spaces.

WordPiece: A subword tokenization method similar to BPE but selects pairs based on maximizing the likelihood of the training data, often marking subwords that don't start a word with a special prefix.